Take Back the Night, Forever and Always

Amelia Meman (they/them and she/her), GWST ’15, is the interim director of the Women’s Center. They have worked in the Women’s Center as an intern, a student staff member, a volunteer, and now professional staff member. This is a loving retrospective on Take Back the Night (TBTN), written in the third spring semester where UMBC has not been able to hold such an event.

Author’s Note: I am proud to say that I have been to every single Take Back the Night since its revival on UMBC’s campus in 2013. This does not mean I am an expert on this event nor that my opinion of Take Back the Night is shared by the thousands who have taken part in this event throughout the past nine years. Because Take Back the Night is such a shared experience, I reached out to some alumni who have experienced TBTN as attendees, volunteers, and leaders. You will see their contributions throughout. Thank you, Yoo-Jin, Autumn, Calista, Hannah, and Sydney.

As we share our spring semester with the pandemic once again, I know I and many of our community members are deeply disappointed to not be able to come together for Take Back the Night. Even more alarming, however, is that many folks don’t know what it is to miss Take Back the Night because they’ve never experienced it.

Our last in-person Take Back the Night was in 2019 and most recently (2021), Jess Myers alongside several student activists and campus partners, created the Take Back the Night Virtual Experience. Before that, the Women’s Center staff and community co-created a zine called “Survivors to the Front,” which invited survivors of gender-based violence to submit their creative works–whether visual art or written word.

These online options have been balms in an otherwise quiet series of Sexual Assault Awareness Months (SAAM) for the Women’s Center. Normally, April is a huge month for the Women’s Center with [at minimum] weekly programming and often a full, month-long calendar of events, workshops, and educational opportunities offered through various departments on campus.

The major event of April (and for many, the entire school year) is Take Back the Night. In the last 3 years, however, we have not been able to host this event. And that’s why I’m writing this blogpost: because it’s been a long time and in addition to cultivating the hope that we can one day bring Take Back the Night back to its glory days as a large in-person, campus-wide event, I hope to preserve just a little bit of this institutional memory.

A Very Brief History of Take Back the Night at UMBC*

In 1971, a group of feminist advocates and survivors hosted the first-ever rape speak-out in New York. A few years later, one of the first “Take Back the Night” marches was held in Philadelphia, PA in October 1975.

UMBC (from what we can tell from the archives), held their first TBTN event in the early 2000s for just a few years. Campus stopped hosting it for several years so as to be in solidarity with other area colleges by participating in Baltimore City Hall’s Take Back the Night. But, by 2013, it made the most sense for us to bring back our own Take Back the Night. So the Women’s Center with support from UHS’s Health Education, Greek Week, and a BreakingGround grant did just that. Since Spring 2014, this campus-wide rally and march against sexual violence has been a signature Women’s Center event every April. Each year the Women’s Center hosts survivor speak-out followed by a campus march against sexual assault. When marchers return, UMBC’s TBTN spends the rest of the evening doing “craftivism” art healing projects and hosting a community resource fair. A smaller version of the Clothesline Project also serves as a backdrop to the evening’s events.

*Thank you to Kayla Smith, who wrote “What You Need To Need Know: Take Back The Night & Its History” in 2017; almost all of this information is from that resource.

How did Take Back the Night work at UMBC?

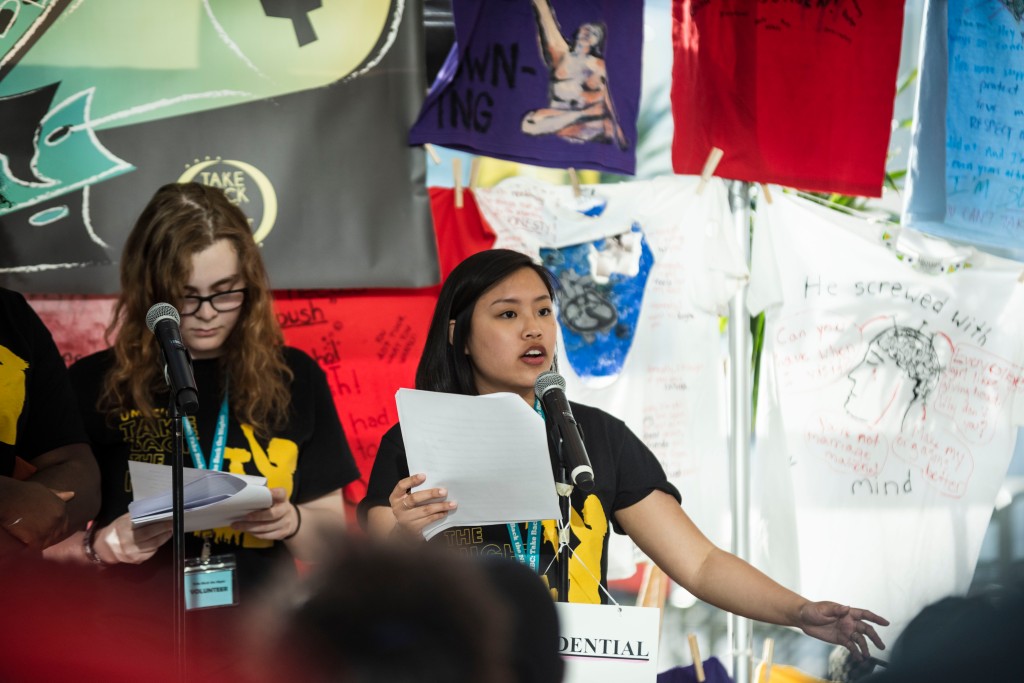

Take Back the Night starts on The Commons’ Main Street with the Survivor Speak Out. On the third Thursday of April, we take over this campus nexus with a mini-Clothesline Project display, microphones, speakers, a ton of folding chairs, resource tables, and hand-painted rally signs. The Speak-Out provides an open opportunity for survivors of power-based violence to tell their stories out loud, in front of an audience.

It was the first time I really identified as a survivor publicly and put myself in that vulnerable position. I remember the wave of emotions while we marched–anger, happiness, relief, anxiety–and how beautiful it was to just feel those things as they came.

Sydney (she/her)

This is a strategic location as it is one of the most heavily trafficked areas of campus. You might ask, “But aren’t the Survivor Speak-Out and the Clothesline Project a little disruptive for all the folks in The Commons?” The answer is yes, and that’s the point. Take Back the Night is placed in such a way that we can bring people together whether they’re attending the event on purpose or walking through and experiencing it randomly.

And that’s how many folks come to be involved in Take Back the Night–they stumble upon this big public event and get wrapped up in the stories they hear over the speakers. For Calista’s (she/her) first speak-out, she was a witness to the power of the event which caused a mixture of emotions: “My first experience felt very comforting seeing others being there for each other. It was also challenging to be in a space that reminded me so much of my trauma — but ultimately made me feel less alone.”

We have heard this reaction echoed in a number of other participants. Survivors are given the opportunity to stand up at a microphone and speak their truth; the result is raw, unfiltered vulnerability and power. Some survivors recall every last detail of their assault. Where it occurred, what they were wearing, who the perpetrator was… Others only talk about what happened in the aftermath. Regardless of what is shared, each person who comes up to the mic speaks their truth and the audience bears witness.

Autumn Cook (M29, ‘21) actually experienced her first TBTN from the front of the stage as one of our TBTN leaders. As a leader, they provide background information about TBTN and also start the Survivor Speak-Out by sharing their own story. Of their first experience, Autumn said:

Jesus. My first TBTN at UMBC was my first year on campus [in 2017]. Before then, I had never interacted with the Women’s Center – either because I didn’t super know what they did or that I was too scared too. But during the lead up to TBTN and aftermath, it felt like I found a family within the Women’s Center. I was one of the intro speakers for TBTN and getting up in front of the massive crowd was fun and illuminating. I was able to share my truth and afterwards I felt loved and seen by everyone in the crowd. The environment of support was like a big warm hug, enveloping and unending.

Autumn Cook (M29, ‘21)

Autumn Cook leads TBTN 2018. Photo credit: Jaedon Huie

Autumn Cook leads TBTN 2018. Photo credit: Jaedon Huie

And still others experienced TBTN by working the event, like Sydney (she/her):

My first experience with TBTN, I was actually interning with The Monument Quilt. I was completely moved by the survivor speak out and the feeling of the community in the air. I remember watching survivor after survivor get up, being struck by their bravery and thinking “I couldn’t do that,” yet feeling heard and seen and accepted regardless. It was also the first true time I think I accepted my own assault and what that meant. I knew [TBTN] was something I needed to be involved in moving forward.

Sydney (she/her)

The resource tables (covered in teal tablecloths) offer information about Take Back the Night and resources for survivors. Photo credit: Amelia Meman

The resource tables (covered in teal tablecloths) offer information about Take Back the Night and resources for survivors. Photo credit: Amelia Meman

Following the energy that builds in the Speak-Out, we mobilize all of the people who have gathered as witnesses and speakers to march across campus and demand visibility, justice, and healing for survivors.

We call on folks to move.

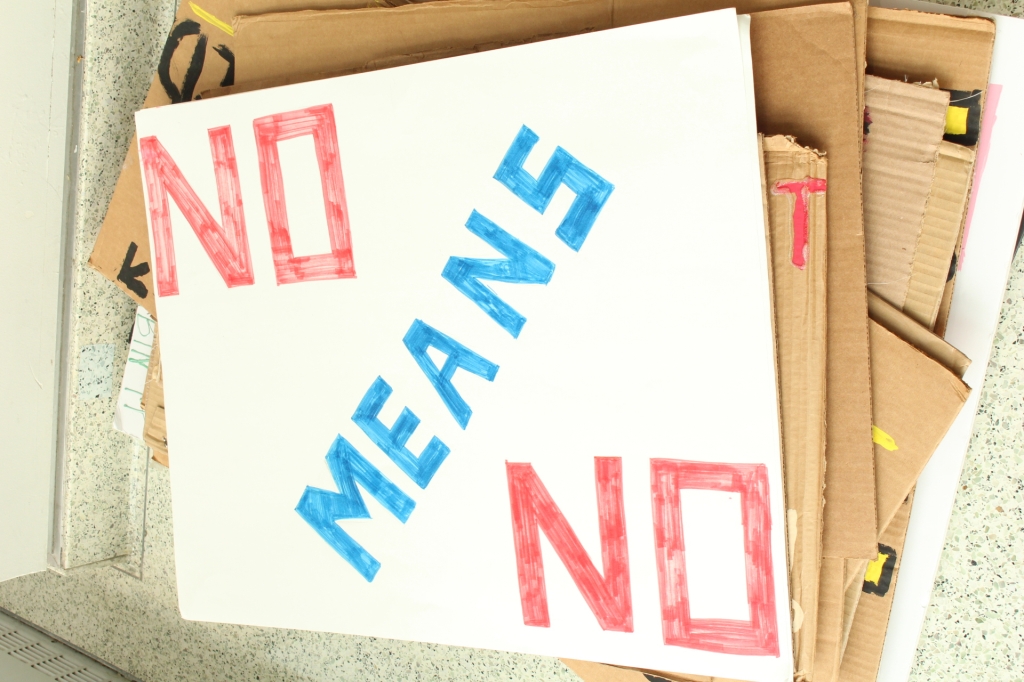

We hand out rally signs to anybody who wants to hold one.

We bring out the megaphones and we line up.

The march is divided with survivors at the front and UMBC community supporters bringing up the back. Marchers are given cards that have different rally chants written on them and line leaders are spread amongst the marchers. Once the march begins, leaders use their megaphones to start chants and direct people along the march route. The number is different at each TBTN, but the march group usually consists of approx. 250 campus community members.

The march is loud and big. Its meant to grab people’s attention, just like the Survivor Speak-Out. Hannah Wilcove, GWST ‘19 remembered her “first encounter was seeing the march pass by me as I was walking back to my dorm freshman year and feeling a kinship with everyone participating that I couldn’t explain. Next year, I wanted to get more involved with the Women’s Center so I volunteered and participated for the first time.”

Many of the people I spoke to have experienced the march from the frontlines and share vivid memories of the emotions that are at play while walking through campus. For Sydney: “It was the first time I really identified as a survivor publicly and put myself in that vulnerable position. I remember the wave of emotions while we marched–anger, happiness, relief, anxiety–and how beautiful it was to just feel those things as they came.”

Yoo-Jin Kang, MLL & INDS ‘15 also remembers the rush as she maneuvered the march around campus: “Leading the march with dearest Kayla Smith. Walking alongside powerful survivors, shouting into a mic, and looking back to see a huge line following behind us. I still have chills thinking about it.”

The march goes all the way around campus starting at the southern entrance of The Commons, going east toward True Grits (and sometimes inside True Grits) and up around the Residence Halls before turning northwards and moving up the hill toward Library Pond. From the pond, the march hangs left to go all the way down Academic Row and stops at the statue of True Grit in front of the Administration Building and The RAC.

Recently, the march has added this stop around the True Grit statue so that marchers can circle up with survivors in the center and allies on the outside. The survivor circle rests with one another while the community continues to bear witness and offer respect.

Healing from trauma isn’t linear, but healing can happen and it does happen.

After regrouping in the circles, the march crosses the Quad diagonally and heads back to The Commons. Once inside, participants are met with a once again transformed Main Street. Where there were chairs and microphones for the Survivor Speak-Out there are now big circular tables with crafting materials available for folks to decompress through art, food and drinks to refresh themselves, and music blasting on the speakers so people can dance it out.

Every part of Take Back the Night is my favorite part, but this ending back at Main Street is really distinct. No matter the feelings that have erupted during the last few hours in the speak out and march we can all come back together to breathe. Breathe. Eat a cookie. Breathe. And laugh.

It might be as biologically simple as the flood of endorphins that comes after something painful or difficult… but it feels magical and powerful. We come back to where we had started… and the space is transformed but so are we. Healing from trauma isn’t linear, but healing can happen and it does happen.

What did UMBC’s Take Back the Night feel like?

It’s different for every person and often different minute-by-minute within the event itself, but for many, TBTN is a time of “firsts.” For Yoo-Jin, “TBTN was one of the first times I saw survivor voices lifted up in a public and unapologetic way. It was the first time I shared about my survivor story in public (and cried lots doing it).” With one of the goals of Take Back the Night being to take up space and push things often shrouded by private shame out into the public space, it can act as a catalyst for many as they work to understand their own trauma and their identities as survivors.

Sydney said that TBTN played a major part in her own identity development and growth as a survivor as it “allowed me to come to terms with the fact that I was sexually assaulted and work through all the emotions that came with it. Over the years attending, I was able to come to terms not only with the event but how I wanted to handle it. I didn’t want to do [the] Survivor Speak-Out but I did want to be there to feel community and then to march and let my story out that way.”

As identity-defining and cathartic as Take Back the Night is… it’s also really and honestly hard.

For as much time as I can take extolling high praise, I could also tell you about how deeply it has rocked myself and so many others that I know. Throughout the event, you are made to listen to stories of violence and abuse. As a witness to the Speak-Out, you play an important part in holding space and honoring others’ stories, but that does take energy and emotional endurance. A lot of people (especially those who shared their stories with me) have been able to reckon with Take Back the Night as something extremely positive, but it can also feel agonizing.

Autumn Cook remembered this duality:

Take Back the Night is a really difficult event to attend. It’s almost impossible to not squirm or react to some of the stories that people share, but that is part of the event. We are all living in each other’s horrendous truths and healing together. You’re supposed to be uncomfortable at TBTN. It means that you’re taking in what is happening and processing it. It’s horrible and liberating and healthy.

Autumn Cook (M29, ‘21)

How has Take Back the Night changed over the years?

One of the most beautiful aspects about Take Back the Night is that it’s always growing with our campus. It grows from year to year. It grows with you. Where Calista started as a spectator, she eventually grew to tell her own story… and then to leading the speak out. Calista spoke of this growth as she recalled how she “struggled a lot with my assault and the process of regaining my voice — but TBTN empowered me.”

TBTN 2019 Photo credit: Winston Zhou

TBTN 2019 Photo credit: Winston Zhou

One person noted that they are still trying to find an outlet similar to Take Back the Night: “I have been looking for TBTN marches or something similar since graduating because I have wanted to share my experience. I don’t think I’d feel ready to do so if I hadn’t participated in it while at UMBC.”

If you look at some of the pictures in this blogpost, you might see the same people show up during different TBTN years. The shirts might look different or their hair might be a little longer. There are different shirts hung up in the Clothesline Project display. The weather during the march goes from sunny to cloudy.

The event has changed each year we’ve put it on to answer the needs and values of our campus community. For example, our march route was adapted to include an accessible route for those with mobility disabilities; previously, stairs were an obstacle for some as they participated in the march. Now we have an accessibility route that is not only available, but has a dedicated volunteer leading folks.

A Personal Reflection + A Conclusion

To be totally honest, I am writing this blogpost for partially selfish reasons… I desperately want to feel the power of Take Back the Night and I am sincerely regretful that I will not have been able to bring Take Back the Night back to UMBC’s campus by the time I start my own next chapter.

There are many reasons why I wanted to work in the Women’s Center and why I love my job now; a big one is Take Back the Night. Over the course of my time at UMBC, I have proudly been present for every single iteration of TBTN since it was revived by Jess and the team in 2013. However, as an undergraduate, I had not yet been able to identify as a survivor nor what I had experienced as abusive.

I worked in the Women’s Center from 2013 to 2015, I was a Gender, Women’s, + Sexuality Studies major, and I had been learning about sexual violence prevention and response work throughout that time but it had never occurred to me to consider my own story and my own experiences. It was only after graduating from UMBC, returning to the Women’s Center as a professional staff member, and a lot of therapy that I began to consider how I might be a survivor… how I am a survivor. My identity and my roles changed–changing my own relationship with TBTN. And TBTN changed again when I began working with student survivors and then again after the September 2018 lawsuit and subsequent Retriever Courage campus activism.

I mention all of this because we are all growing. We are all welcoming new aspects of ourselves–and similarly, Take Back the Night is bound to change. The power Take Back the Night has is in the change it creates for each person who interacts with it.

The power Take Back the Night has is in the change it creates for each person who interacts with it.

Right now, Take Back the Night looks different because it must, but that’s not a death sentence so much as it is an opportunity to welcome and cultivate change.

Perhaps, Take Back the Night will resume its live, in-person status in the Spring of 2023. I have hope that it will. And as much as I worry that it won’t look or feel like the Take Back the Night that I remember… the shared memory that people like Autumn, Sydney, Yoo-Jin, Hannah, Calista and I will continue to hold power and the institutional history of Take Back the Night will only grow. And that’s where the magic of TBTN is and always has been–with the people who are there to witness, the people who speak truth to power, and the people who demand space, time, energy for radical acts of healing.

More information about UMBC’s TBTN:

What You Need to Know About Take Back the Night Series

Posted: April 29, 2022, 4:23 PM