Environmental Justice and Sustainability in Baltimore

On a hot summer day in Curtis Bay, the air feels thick, not just with humidity, but with the smell of diesel, chemicals, and burning trash. For many residents, this isn’t just unpleasant; It’s a daily threat to their health.

“We want to open windows. Windows should be open. People should feel a breeze. People should feel comfortable walking in their community and not worrying about what they’re breathing in,” says Shashawnda Campbell of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust.

Extreme heat, sea-level rise, polluted waterways, and air pollution are just a few of the environmental issues that Baltimore residents face. As an industrial port city, Baltimore has a history of heavy industry, shipping, manufacturing, and transportation. The city’s waterways still suffer from pollution caused by generations of industrial pollution, leaks from aging separate sewer and stormwater infrastructure, extensive hardscape (paved areas), and widespread littering.

Air pollution is another significant cause for concern, particularly in South Baltimore communities, which lack adequate public health regulations. As a result, many industries were able to move in and set up more industrial projects with hazardous environmental byproducts. A particularly concerning facility is the waste-to-energy incinerator in Westport, which significantly contributes to local pollution. It is the 10th-largest trash incinerator in the country and accounts for 36% of all air emissions from Baltimore City industry. It is thought to be “green energy” because it converts waste into energy, but it actually has devastating effects on air and health quality. However, despite being marketed as sustainable, incinerators emit toxic pollutants like mercury and lead. These facilities often receive subsidies for being “renewable energy” while harming the very communities they claim to help.

Industrial facilities, including coal terminals, waste incinerators, and heavy diesel traffic, have long burdened residential communities like Curtis Bay, Brooklyn, and Westport. These facilities contribute to air and water pollution, adversely affecting the health and well-being of residents. The environmental burdens in South Baltimore have led to notable public health issues. Residents experience higher rates of asthma, cancer, and other chronic illnesses linked to pollution. For instance, the presence of coal dust in Curtis Bay has raised significant health concerns among community members.

Historical practices like redlining have played a significant role in this disparity. Redlined areas were systematically denied investment, leading to economic decline and making them targets for industrial development. Consequently, these communities, predominantly inhabited by Black and low-income residents, have faced environmental neglect and degradation.

The maps above depict the white neighborhoods that form the shape of an ‘L’ which accumulate structured advantages, while Black neighborhoods, shaped in the form of a butterfly, accumulate structured disadvantages (Brown, 2016).

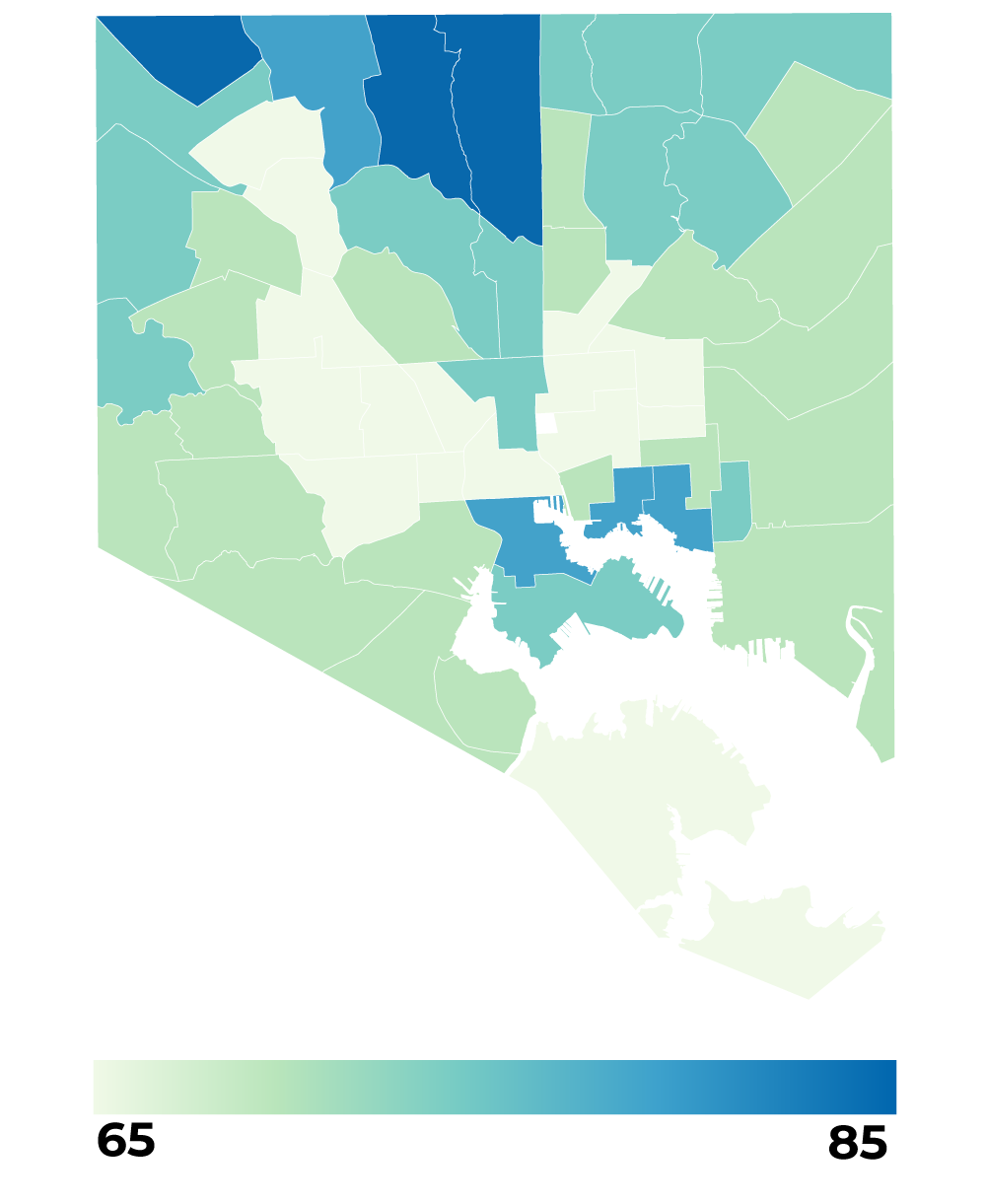

Average life span of area residents.

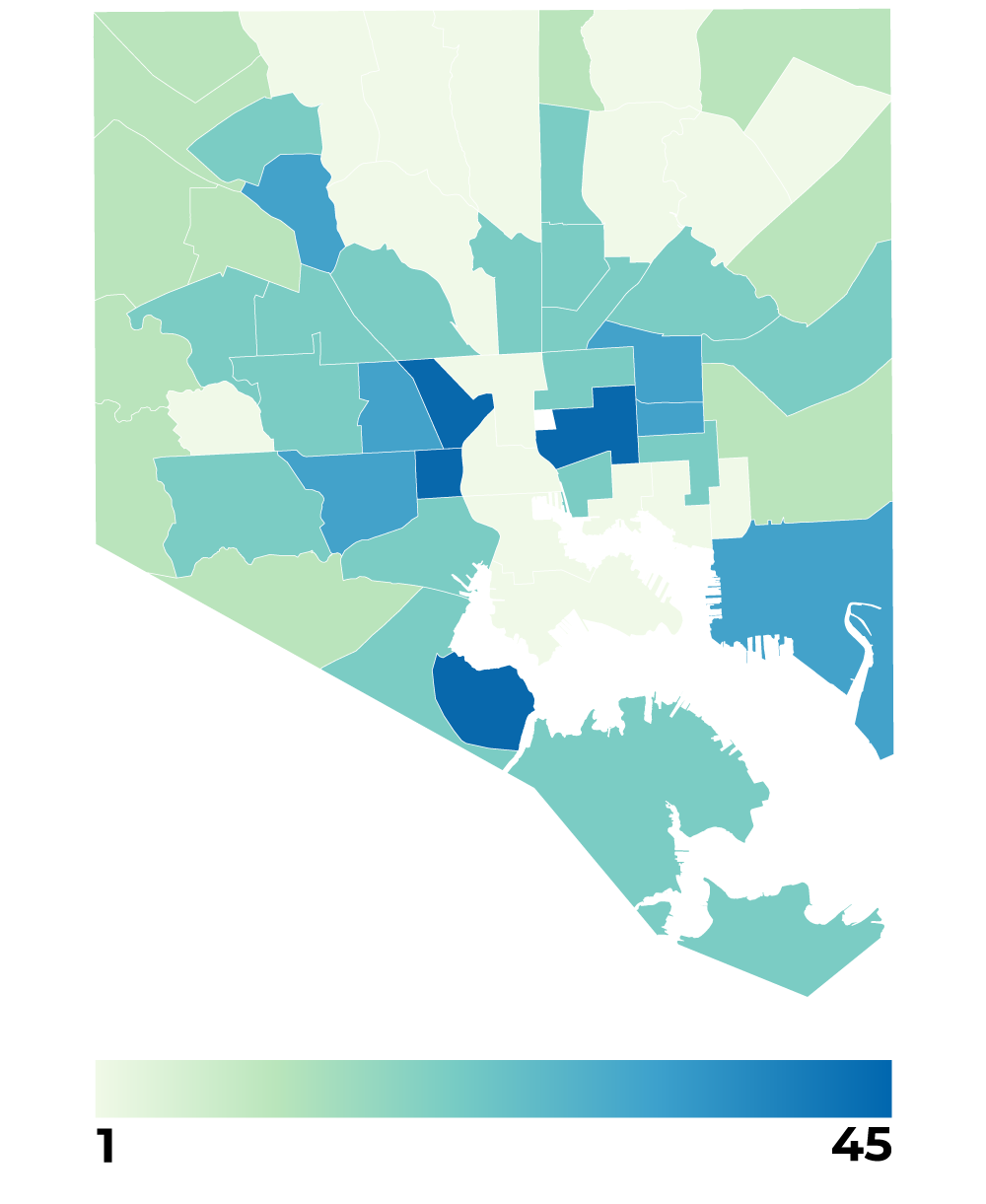

Average life span of area residents. Percent of families living below the poverty line.

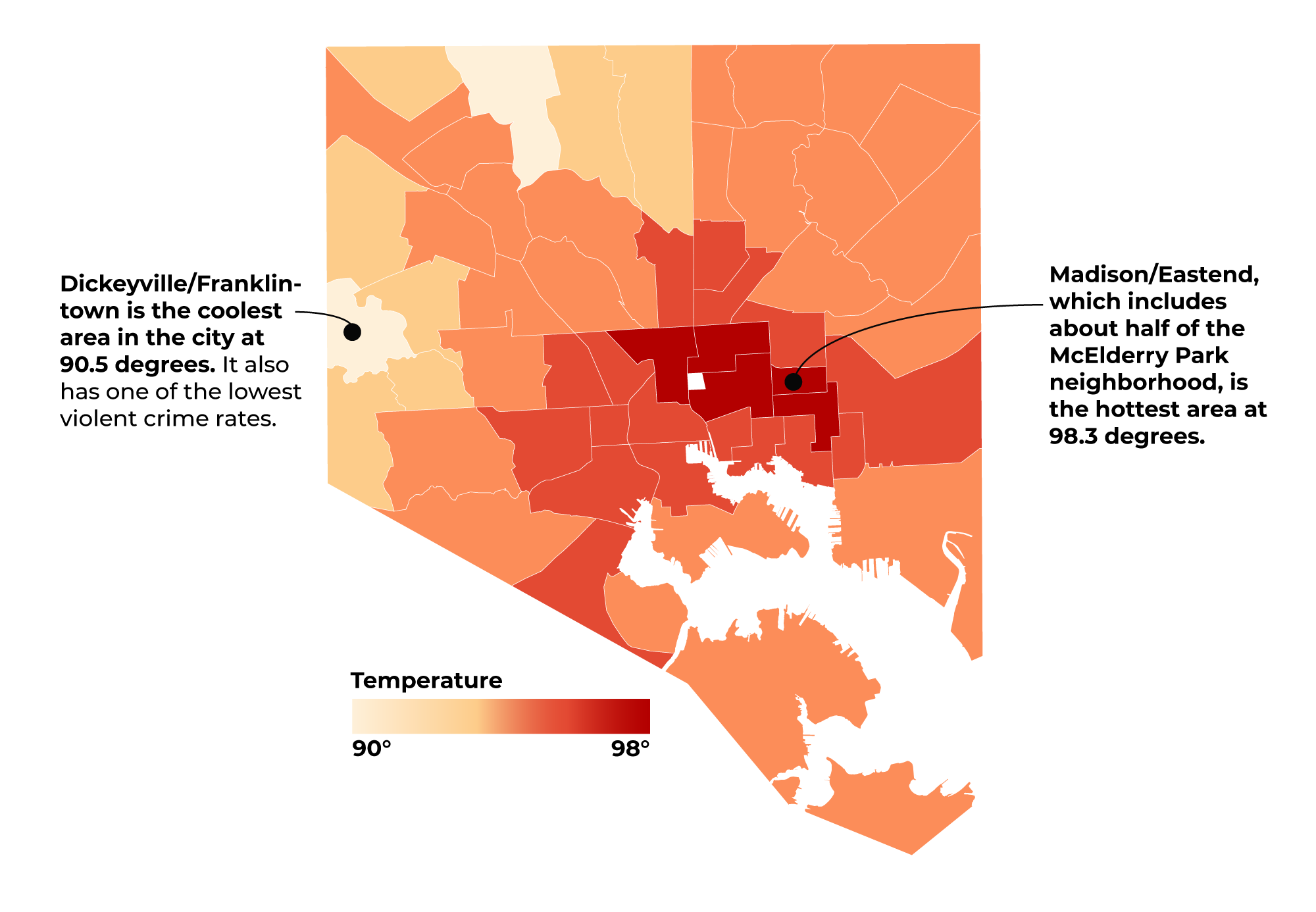

Percent of families living below the poverty line.The graphs above depict data from a federally funded study that took block-by-block temperature readings in August 2018. People who live in the hottest parts of the city are more likely to be poor, to live shorter lives, and to experience higher rates of violent crime and unemployment.

These temperature disparities stem from a lack of green infrastructure, grassy areas, tree canopy, and other vegetation. Green spaces in urban areas can significantly reduce temperatures through various mechanisms, primarily by providing shade and increasing evapotranspiration. This cooling effect helps mitigate the urban heat island effect, where urban areas tend to be warmer than surrounding rural areas. Vegetation removes chemicals and filters particulate matter from the air. It significantly reduces flooding by intercepting and slowing down rainfall, allowing more water to infiltrate the soil and preventing surface runoff.

Despite challenges, communities have actively worked to resist environmental injustices. Organizations like the South Baltimore Community Land Trust have been instrumental in advocating for cleaner environments and equitable development. Their efforts include opposing the construction of new incinerators and promoting zero-waste initiatives. In Curtis Bay, community-driven research has been launched to monitor air quality and hold polluters accountable. These initiatives empower residents to collect data, engage in policy discussions, and push for systemic changes to improve their living conditions.

Moving forward

Addressing environmental justice in Baltimore requires a multifaceted approach:

Policy Reform: Implementing stricter regulations on industrial pollution and ensuring equitable enforcement in all neighborhoods.

Community Engagement: Supporting grassroots organizations and amplifying the voices of affected residents in decision-making processes.

Investment in Infrastructure: Allocating resources to improve housing, healthcare, and environmental conditions in historically marginalized communities.

By acknowledging the historical context and actively working towards equitable solutions, Baltimore can move towards a more just and healthy future for all its residents. Sustainability must go beyond solar panels and recycling bins. It means clean air and waterways, trees and parks, and making neighborhoods safe and livable. It means investing in communities, not displacing them.

How I got involved

My passion for environmental justice sparked after taking GES 350 (Climate Change & Society) at UMBC with Dr. Dawn Biehler. This was the first class I had taken that discussed environmental racism and the disproportionate effects of climate change on different human populations. We learned about how low-income and communities of color are more vulnerable to climate change than affluent and white communities.

Oftentimes, we learn about global impacts of climate change like polar ice caps melting, extreme weather events (hurricanes, wildfires) etc. But for many of us, we don’t see the direct impacts of climate change, making it harder to care about environmental justice. However, Dr. Biehler’s class was the first time I learned about environmental issues in Maryland. Being born and raised here, I was shocked to learn about the devastating decades-long impacts on vulnerable populations, especially in Baltimore.

After spending some time learning about these issues, I decided to develop a program for the 2025 Alternative Spring Break trip through UMBC’s Center for Democracy and Civic Life. My co-leader and I spent months planning a five-day trip for UMBC undergraduate and graduate students to learn about environmental justice and sustainability in Baltimore city. Throughout the trip, we met with nonprofits, community leaders, elected officials, and others. The group included everyone from freshmen to Ph.D. students, all from different cultural and academic backgrounds. Each person brought their own experiences and unique perspectives to understanding environmental justice and sustainability. A senior graphic design major talked about wanting to use their passion for environmental justice and graphic design to create art that envisions a more sustainable future. A graduate engineering student thought about implementing sustainable practices in engineering, bridging the gap between the two. A freshman political science major was passionate about advocating for better policies to address the inequities we learned about during ASB.

When it comes to activism, many of us (myself included) have a hard time considering ourselves capable of being “activists.” We tend to think of activism as leading protests and marches in D.C. or staging a sit-in. And while those are valid ways of engaging in activism, there are so many other possibilities. You don’t have to be an environmental scientist to engage in environmental activism; we all have unique positions and skills to contribute.

Through UMBC courses and programs like Alternative Spring Break, I’ve learned that real change begins with recognizing our collective responsibility. Whether you’re an artist, engineer, or policy student, your voice and skills matter in the fight for cleaner air, safer neighborhoods, and a sustainable future.

Posted: June 12, 2025, 10:50 AM