More Than a Band-Aid: LGBTQ Health Inequity

A reflection by Shira Devorah, Women’s Center Student Staff

Going to the doctor is never fun; most people dread pesky checkups getting in the way of their day. While medical appointments can feel like a nuisance to some, for many people in the LGBTQ community, just seeing a doctor can be dangerous.

Saying that structural health inequity in the U.S. is a problem is an understatement, as many people face huge barriers when it comes to receiving adequate care. Women, people of color, people with lower socioeconomic statuses, fat people, elderly people — the list goes on and people continue to suffer. While I’m specifically highlighting a few of the issues surrounding queer care, it’s important for people to know that this is just one flawed aspect of a flawed system. To fight for justice, we must demand competent care for all people.

So before we all go kicking down the doors of the nearest hospital, let’s discuss what the issues actually are. Why is it so difficult for queer people to get the medical help that all people deserve?

Here are just a few reasons:

1) There’s a large element of risk that queer people must face when it comes to taking care of our health.

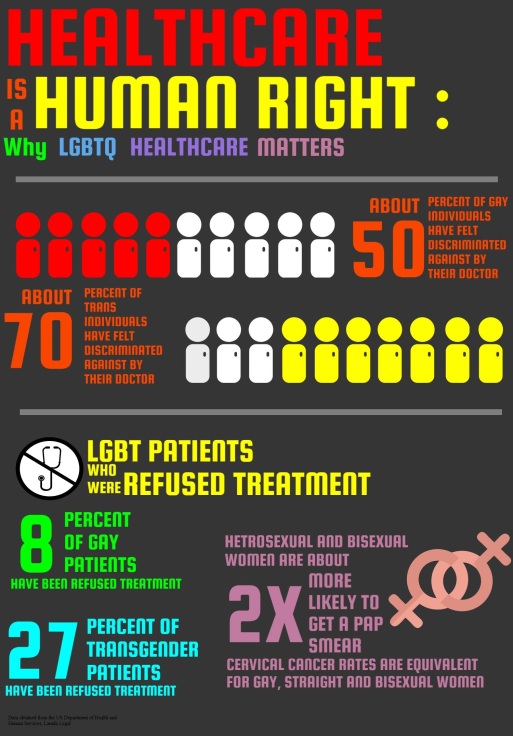

Stigma, discrimination, violence, and even denial of care are all real issues that can dissuade people from seeking help in the first place. According to Lambda Legal’s 2010 survey, over half of LGBTQ respondents felt discriminated against when receiving care. Getting to receive care at all, let alone good care, can be very difficult for queer individuals who have poor access to health care. There are huge health discrepancies in LGBTQ populations, especially for older people and transgender individuals.

As a queer person who usually isn’t read as queer, I’m very lucky that I haven’t had to fear going to the doctor (besides a healthy fear of getting shots). Here’s why:

- I’m a lazy femme, so I don’t get the strange looks from doctors assessing every inch of me that gender nonconforming individuals might get.

- If the doctor asks about my sexual history, I may blush, but being a bisexual cis woman in a monogamous relationship with a cis man means that the kind of sex I would be discussing wouldn’t be considered outside the bounds of heterosexuality.

- I haven’t had reason to fear outing myself through discussing my experiences.

- If I have a problem with my genitals, I only have to worry about the coldness of the speculum, not that my gender identity is being questioned or invalidated.

These are just some reasons why going to the doctors is so difficult for many people who do not have this privilege.

Credit: Philadelphia Lesbian Virtual Magazine

2) There’s a huge gap in medical knowledge, especially for queer people and women.

No matter how nice or accepting a medical professional is, they may not always know how to treat a queer person. Medical schools in the U.S. spend so little time on LGBTQ-related content. Often times, medical students are taught that sexual behaviors of LGBTQ people are risky, which perpetrates the narrative that gay people are ‘diseased’. Doctors aren’t free of biases and such misunderstanding can get in the way of someone getting adequate care.

Many doctors have very limited experiences with transgender issues. Insurance companies will refuse to sign off on HRT or surgeries that some trans people really need. On the flip side, the medicalization of transgender identities suggests that all trans people have to have surgery to be considered more “legitimate,” which is not possible nor desired for many trans people.

Credit: “When Healthcare Isn’t Caring” Lambda Legal 2010 Report

3) Gender and sexuality are areas in which medicine can be negligent.

A lack of medical knowledge surrounding certain populations is a problem, and not just for queer people. Did you know that there is a huge gender gap in medical research and clinical trials? Medical research is lacking valuable data on women’s issues. We don’t even know for sure what a heart attack looks like for a woman because of countless misconceptions. This gap in knowledge, coupled with gender biases, seriously affects medication, care, and diagnoses that women receive.

credit: Transgender Law Center

When gender and sexuality collide (as they often do in most humans), things get complicated. Aspects of personal identity intersect, creating an even bigger gap in medical knowledge. Medicine has historically failed queer people, and a lot of effort is required to improve care for the future.

Okay. Deep breaths all around. This is some heavy stuff.

Luckily, there are also a lot of options where LGBTQ healthcare is pretty amazing. There is a substantial list of resources at the end of this post, so check them out! Good options do exist, even though access to these options may be limited for many.

Students here at UMBC have pretty accommodating facilities. University Health Services has a very dedicated and helpful staff of professionals who are trained to work with all kinds of student populations. Almost the entire medical staff is made up of women, and personally I’ve found the practitioners to be gentle and attentive. UHS is consistently making an effort to improve, and while it is by no means a perfectly accessible center, attempts are being made.

Our medical space on campus may be generally positive, but we also have to be aware doesn’t change the negative experiences that many people can face elsewhere. Some may be too scared of going to UHS because of past trauma or maltreatment. Even though UHS is a great resource, the training and education for all medical practitioners is still lacking, and it’s possible to come into a campus medical center without being fully prepared to treat all kinds of people.

In Peer Health Education, the inclusiveness of LGBTQ issues is lacking, especially when it comes to discussions of sexual health. A big initiative that the sexual health committee is undertaking now is to revamp the current programs to be more inclusive to people of all sexualities and gender identities. Recently, I created a survey in order to assess how LGBTQ people feel about sexual health education on campus. I’m hoping that this will foster a productive discussion with other queer UMBC community members so that we can work together to make important changes to the health education curriculum. While this is in no way a quick fix the huge problem of LGBTQ health disparities, it’s always good to think globally and act locally.

HAART poster, discussing how stigma against people with HIV can be incredibly damaging.

Everyone has the right to be treated respectfully and competently when accessing health care. Even though my experiences with doctors have been generally positive, I can’t say the same for many other queer people. What I can do is speak up about the problems that I know exist, and do my best to contribute to change. As a peer, as a queer, and as a person devoted to justice, I want to use my privilege and opportunities to work towards a better system. I just hope that one day the only thing people have to fear when walking into a doctor’s office is as simple as a shot.

**************

Check out these great resources!

- Chase Brexton Health Care has locations all around Maryland, with a main branch in Baltimore. This clinic has a health center that specializes in the specific medical needs of LGBTQ people.

- GLMA has a provider directory that can help guide people to LGBTQ competent doctors and services, including psychologists and counselors who specialize in LGBTQ mental health.

- The National LGBT Health Education Center at Fenway Institute has a continuing education program designed to educate medical professionals on how to address the needs of LGBTQ individuals. The American medical association has this comprehensive

- LGBTQ resource list full of helpful information- from patient resources to statistics and studies done on disparities in LGBTQ care.

- Do you identify as LGBTQIA? Come to a roundtable discussion about LGBTQIA+ issues in health education on April 20th from 4:30-5:30pm at the Women’s Center, and help Peer Health Educators make more inclusive changes to health education on campus.

Posted: April 11, 2016, 3:37 PM