Survivorship Looks Different in the Asian American Community

Samiksha Manjani is a Student Staff member at UMBC’s Women’s Center. She is a Political Science and Sociology double-major and is currently a co-facilitator of the Women’s Center’s discussion group, Women of Color Coalition.

As a survivor of sexual violence, I have found myself re-traumatized by the recent events that have happened at UMBC. In the aftermath, I struggled to focus in my classes and could barely complete my work. Despite this, I somehow managed to get by with everyday going by in a blur. I went through the motions day-in and day-out. I was slowly sinking back into depression.

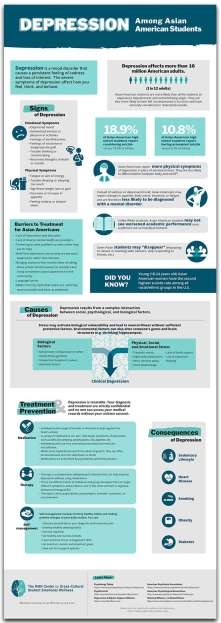

One of the most common emotional and psychological responses to sexual violence is depression (RAINN). Depression is a mood disorder which occurs when feelings of sadness and hopelessness persist for long periods of time and interrupt regular thought patterns. It affects a person’s behavior and can disrupt their relationships. Just like many other survivors, I also struggle with depression.

During this difficult time, I was shocked that no one in my life had asked me how I was doing. None of my friends had asked me how I was handling the news, despite knowing that I’m a survivor and that I also struggle with depression. They knew about the lawsuit against UMBC too. In fact, they knew so much about it that they talked to me about their opinions on the matter. Yet, they never asked me how I was processing the news or if I was doing okay.

At first, I thought, “wow, I have really shitty friends in my life.” But I realized that this was a drastic conclusion to make considering my friends were normally compassionate. Instead, I tried to put myself in their shoes. Why would my normally compassionate friends be so inconsiderate? Had my external behavior reflected my internal suffering?

I realized that, from an outsider’s perspective, I seemed completely okay because I went to my classes and work as usual. My behavior, communication, and demeanor had basically stayed the same so nothing seemed amiss. However, this was completely contrary to how I felt internally. Inside, I felt awful. Every step I took was harder, every assignment I completed took longer, and every smile was faker. I was falling apart on the inside, yet no one around me could see it.

At first, I thought that this was just how I expressed trauma. But after some reflection, I realized that I knew so many other Asian women dealing with depression that were also still high-functioning. I was not the only person who exhibited depressive symptomology this way, and more importantly, it had seemed that this was especially common for other Asians.

My assumption was not wrong. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (2011) found that Asian-American teenage girls have the highest rate of depression compared to any other racial, ethnic or gender group. Furthermore, the suicide rates for 15-24 year old Asian American females are 30% higher than the rates for white females of the same age (Mental Health America). Yeung and Kam (2006) found that none of the Asian patients in their study considered depressed mood as their main problem. However, more than 90% of them indicated having a depressed mood when asked to rate their symptoms on a depression rating scale.

Despite these alarming statistics, 51% of Asian Americans have at least a Bachelor’s Degree, compared to 29% of all Americans (Mental Health America). Furthermore, 21% of Asians, ages 25 or older, have attained an advanced degree (e.g., Master’s, Ph.D., M.D. or J.D.), which is significantly higher than the national average of 12% (Baum and Steele, 2017; United States Census Bureau, 2016). Lastly, the median annual household income of Asian American households is $73,060, compared to $53,600 among all U.S. households (Pew Research Center, 2017). It is important to note, however, that there is variation in educational attainment and median annual income among the different ethnic groups which makeup “Asian Americans.”

These findings made me wonder, why do Asian women express depressive symptomology so differently than other ethnic groups?

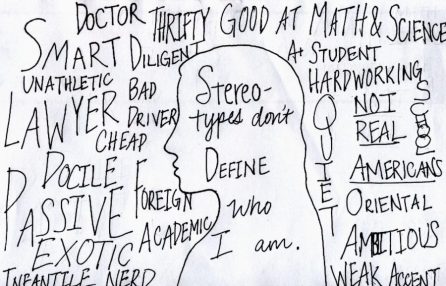

One reason could be because of the immense pressure Asians deal with to live up to the model minority stereotype. The model minority stereotype characterizes Asians by hard work, laudable family values, economic self-sufficiency, non-contentious politics, academic achievement, and entrepreneurial success (Kang, 2010). There is a lot of American cultural pressure on Asians to fit into this “intelligent and self-reliant” stereotype. Such a stereotype has dire consequences; for-example, Asian students are pressured to rise to an academic bar that keeps rising. The mental health cost of reaching an unrealistic standard is demonstrated by the statistics mentioned above.

This pressure is worsened by the fact that many Asian immigrants experience downward economic mobility upon arrival to the U.S. Most Asian immigrants are highly educated and held middle-class status in their country of origin (Lopez, Bialik, & Radford, 2018). Because of this downward shift in class status, Asian immigrants have to work their way up from the bottom of the social and economic ladder in the U.S. This is a very daunting task given that many Asian immigrants not only have to support themselves and their families in the U.S., but also relatives back home (United Nations, 2017). This leads to an immense pressure to climb up the socioeconomic ladder and become financially stable.

Both the pressure of the model minority stereotype and pressure to support family members removes any possibility for Asians Americans to display characteristic forms of depression without severe consequences. There are high costs for Asian American immigrants if they do not complete their education, capitalize on job opportunities, and/or perform at their jobs. If they do not perform, they are risking not only their survival, but the survival of relatives back home. This does not mean that people who display traditional depressive symptomatology are somehow less “able” or “motivated” if they can’t complete these tasks. It is simply that the pressure to economically succeed robs Asian Americans the ability to address mental health concerns.

Another reason could be the large stigma within the Asian community surrounding mental health illnesses and treatment. Asian Americans are 3x less likely to seek mental health services than White Americans (Nishi). Furthermore, it is taboo within the Asian community to speak about having mental health illnesses (Chu & Sue, 2011). One large reason this stigma exists is because of the concept of familial shame within Asian communities.

There is immense pressure in the Asian community to preserve the family’s reputation and status at all costs. This is reflected in popular terms used within various Asian cultures which represent the process of shame or losing face: “Haji” among Japanese, “Hiya” among Filipinos, “Mianzi” among Chinese,”Chaemyun” among Koreans, and “Sharam” among Indians (Sue, 1994). If an Asian person has a mental health illness, it could be interpreted by the community as a result of their family’s failure to raise the person correctly. Therefore, Asian Americans are unlikely to acknowledge and seek mental health treatment in fear of “bringing shame” to their families.

I think in a lot of ways all of these factors have influenced the way that I have processed the trauma of my assault and the resulting depression. Like many other Asian American women, I don’t outwardly exhibit depression through conventional symptoms. However, this doesn’t mean that I experience depression less severely than other people. On the contrary, I struggle with depression so much sometimes that it’s hard to even do basic tasks (even if I end up somehow getting it done). Because of the fact that depression is one of the most common psycho-emotional responses to sexual violence and also that the Asian community presents unique depressive symptomology, it is logical to conclude that survivorship is likely to look different in the Asian community.

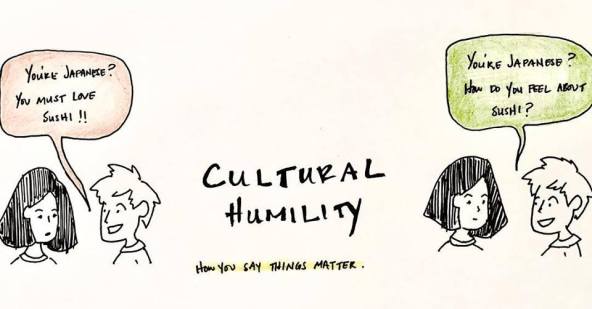

Therefore, it is extremely important for friends, family members, and mental health professionals to recognize that survivorship manifests differently in various ethnic communities. As such, the type of support given must be individualized to meet the needs of survivors of different backgrounds. To best support survivors, the people within the survivor’s inner circle should adopt a lens of cultural humility.

The Women’s Center uses this lens of cultural humility to best support survivors of different backgrounds. Cultural humility is a humble and respectful attitude towards individuals of other cultures that pushes one to challenge their own cultural biases. This departs from “cultural competency” in that it recognizes that a person cannot possibly know everything about other cultures. Instead, people should approach learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.

I truly believe that if my friends had adopted a lens of cultural humility, they would have easily picked up on my struggles. If they had understood more about Asian culture and what it means to be an Asian immigrant, they probably would have been able to recognize my signals of distress. This is especially important for mental health professionals; they would be able to pick up more details from their clients if they held the mindset that “there’s always more to learn.” Using this lens, we can better support the survivors in our lives.

**Please note that not every Asian person experiences depression this way. The goal of this blog is to highlight a common phenomenon in the Asian community. If an Asian person does not process depression or trauma this way, it is not a reflection of their Asianness, intelligence, reliability, or any other characteristics.**

Posted: November 1, 2018, 1:25 PM