Parental Guidance Necessary: Gender Equity in Parental Leave

Alexia Petasis is a student staff member at the Women’s Center. Alexia is pursuing an individualized studies degree with a concentration on social justice and dance. She is a co-facilitator for Pop-Culture Pop-Ups.

Alexia Petasis is a student staff member at the Women’s Center. Alexia is pursuing an individualized studies degree with a concentration on social justice and dance. She is a co-facilitator for Pop-Culture Pop-Ups.

Originally with this blog I wanted to to explore the ways in which the gender wage gap could be mitigated by giving fathers the same parental leave policies as new mothers. However, as I started researching I found that there many more benefits than pay equity; more equitable parental leave policies have the capacity to end the traditional gendered division of labor.

In order to talk about this issue through an intersectional feminist lens, I want to add a disclaimer about the language I use in this blog post. I will be referring to mothers as those who give birth and fathers as those who co-parent with mothers; however, this is a heteronormative and cisgender-centered assumption. There are many different people who give birth who may or may not identify with the label of “mother.” In spite of this, our language for parental leave policies has remained stagnant which is a problem in and of itself. I will be dividing my conversation among “maternal” and “paternal” conceptions of leave as they are articulated by policy, but I hope that I can also offer space to challenge those conceptions and show the diversity in sets of parents that exist in the world.

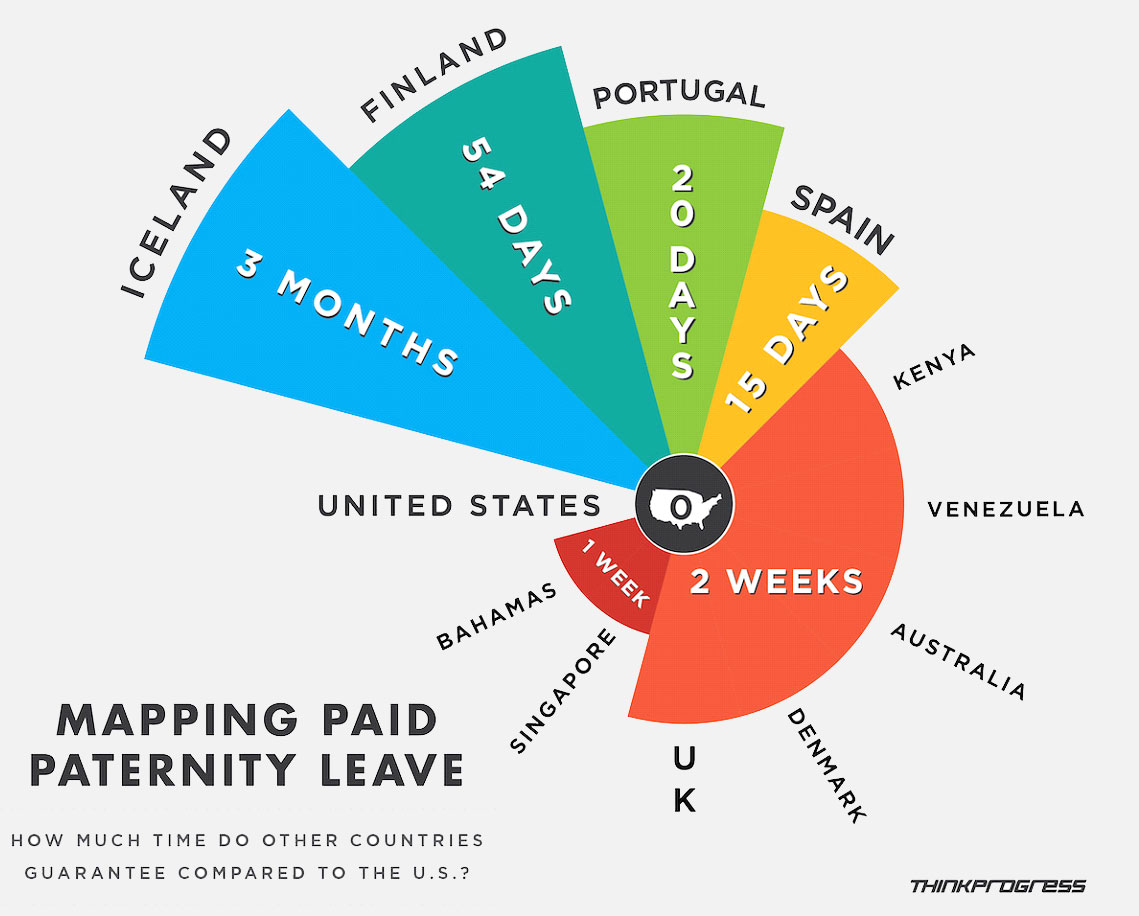

Let me start with explaining what paid paternity and maternity leave is and what our policies are here in the United States. Paid paternity and maternity leave is when new parents have access to a select amount of paid time off after having children. Obviously, the time given off for new mothers or those who give birth fluctuates based on their employment and which state they live. On average, based on the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), maternity leave can ensure up to 12 unpaid weeks off. In the United States, we currently do not have any policies in place to give mothers paid time off or fathers any time off, paid or unpaid. This discourages new parents from taking any time off work after having a child. Having only the mother stay at home with the new-born child perpetuates the stereotype that the father is the breadwinner of the family (this is further complicated when we think about lesbian and gay couples raising children). Mothers might only take a limited period of time off, they might take off and then stay home for a while and rejoin the workforce, but regardless there are usually consequences to any time off they take. Women in the workforce also face pregnancy discrimination, which results in being fired, not hired, or otherwise discriminated against due to being pregnant or intending to become pregnant.

To give some context to how this is related to eliminating the wage gap, experts argue that the wage gap is not only due to women getting paid less on the dollar than men, but because of the “motherhood penalty.” This penalty is the effect of the time women take off from their work after having children and the negative impact it has on their ability to get promotions, get raises, or gain more years of professional experience. While there are plenty of women that go back to work soon after they have children, women are often still the ones who engage in childcare work or unpaid domestic labor while still doing professional work, known as the “second-shift.”

For an issue as complex as this one seems, it actually is not too hard to see how gender norms are deeply ingrained in us growing up and how the policies then reflect that. For example, growing up I am sure you were relegated to play with certain types of toys based on your assigned gender. For me, that meant playing the stay-at-home mom with the very realistic baby doll I had, being gifted an ironing board playset, and spending my free time pretending to be an elementary school teacher. Clearly, all these toys and pretend games had a theme; they were all things I had seen the women in my life doing. They were tasks that involved staying in the home, taking up childcare responsibilities, and embodying the caring and nurturing traits that women were expected to hone and perfect. In contrast, my brother had a range of different Superman, Batman, and Spiderman costumes he would dress-up with alongside a collection of hot-wheels race cars. Now, if we think about the gendered division of toys and play, we can understand what society expects out of us solely based on our gender.

Reflecting on this dichotomy as a 21-year-old, I cannot help but also note the irony of how I have grown into an adult woman: the fields in which I have the most work experience are babysitting and teaching.

I use this as an example to demonstrate the harm that arises when we grow up thinking our talents, abilities, and traits are determined by our gender and the expectations that we believe we have to abide by when wanting to have a family. I’d also like to bring up the hetero-normative structure of these policies since the expectation is having a mom and dad, but the reality could be having two moms, two dads, a single parent, or two non-binary parents. Instead of the division of labor being equal and both parents being confident in their ability to stay at home and raise a child, that responsibility is socially cemented as women’s work. In doing so, men stay at their job and advance their career while moms face the consequences of their time off, and those fathers actually receive higher wages after having a child, known as the “fatherhood bonus.”

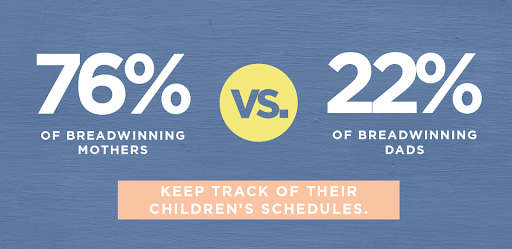

Regardless of whether the mom stays home for a bit, goes right back to work, or the parents hire a nanny, working mothers almost always engage in the second shift, something I have seen in my countless years of babysitting. Mothers and fathers might work the same amount of hours a week but whereas a father is only expected to work and then come home, the mother makes sure dinner is made, the house is cleaned, the kids are picked up, and everyone in the family and home is in order (which often involves a heavy emotional and mental burden).

Paid paternity leave policies would not only benefit new-fathers in hetero-sexual relationships it also benefits new fathers in non-heterosexual relationships, where both parents are fathers and in relationships where the father is the one giving birth. In Soraya Chemaly’s book, “Rage Becomes Her:The Power of Women’s Anger” she discusses how in LGBTQ relationships, parenting relationships are usually more egalitarian unless there’s a stronger butch/femme expression of gender, in which case the disparity of parental duties begins to resemble heterosexual partnerships more clearly. Giving all new parents paid leave, no matter their relationship to their partner, could result in cultural shifts that give space for all types of parents to be present in the beginning of their children’s lives.

I was motivated to write this piece as a personal way to reflect on parental relationships that I have seen who did not divide childcare responsibilities equally and observed the unfair expectations for mothers to “do-it-all.” I wanted to tie in how that mentality hinders any progress for an equitable home and workforce.To do so, I had to look back on how my gender shaped so many aspects of my personality and how I always thought the traits of caring and nurturing just came easily for me. This realization pushes me to consider how I will raise my children in a way that rejects this gendered expectations of emotional labor, childcare, and professional work. Moving forward, my hopes are that an equitable parenting relationship is respected by my partner and my workplaces.

This gets me back to my main point. In order to create equality in the workforce and at home, policies should ensure that both mothers and fathers receive equal paid time off after having children. This would reward and motivate parents to take their time off and engage in the responsibilities of being parents. It would also mitigate the motherhood penalty and pregnancy discrimination as now both men and women would be expected to leave their place of work when they have a child. Furthermore, it would create a new generation of men that will not shy away from care-taking and embrace their abilities to be nurturing.

Check out these resources to learn more about the topics that were covered in the blog:

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/01/the-daddy-track/355746/

Posted: May 13, 2019, 3:07 PM